Anniversary of the ‘Battle of Boyle’

The sad end to the life of Brigadier Michael Dockery, Sgt Frank Balfe and Miss Ellen Nolan needs talking about.

(By Paul Malpas, Connaught Rangers Association)

Ireland and its people now know all about the 10 years of horrible conflict from 1914 to 1923 when Ireland’s young men fought above their weight in international and domestic warfare. In history the whole has been blended into one decade of destruction but the last year of that decade is not talked about. Four or five generations of school children have had this year wiped from the syllabus and know nothing about the battle that sent neighbour against neighbour, father against son, brother against brother. From an Irish point of view this year was probably the most important year in this decade of slaughter.

The events of this year might make people talk, might get the ball rolling, might make the upcoming centenary of events in the civil war in Ireland a time for remembrance, a time for forgiveness. I as an Englishman, albeit with Irish connections, might be better at explaining it than an Irishman who could be accused of taking sides.

The treaty that Michael Collins and Arthur Griffiths signed in December 1921 led to an almost 50/50 split in IRA ranks with a vote of 64 for the treaty with 57 against in the Dail in January 1922. The objections were:-

- That an oath by an Irish government had to be given to the King, George V

- There was to be a partition of Ireland. Most of Ulster to remain with the UK.

- Ireland was to be a dominion of the British Empire, like Canada and Australia.

- Britain to retain the strategic treaty ports on the south coast.

The pro-treaty men realised these conditions could, with diplomacy, be nullified over time. However the anti-treaty men wanted the whole of the cake then. Something they had been fighting for since 1916.

In the General Election called to ratify the treaty on 18th June 1922, the Free Staters or pro-treaty politicians won a sizeable majority of 239,193 against 133,864 anti-treaty votes. There were 132,570 votes to the Labour Party who refused to play any part in the discussion but secretly favoured the treaty and there were 114,656 votes to a lot of smaller parties who again secretly favoured the treaty. So the will of the country was for what the Collins/Griffiths axis realised what they thought best for Ireland. Unfortunately the anti-treaty men were belligerent and importantly lightly armed enough to give them confidence in a battle.

However before the election the anti-treaty forces seized the Four Courts, the seat of Ireland’s justice system on the 14th April 1922. The Provisional Government led by Collins left them there, like a stone in their shoe, until after the election. Under pressure from Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, Michael Collins ordered General Richard Mulcahy to storm the rebels in the Four Courts with artillery given by the British. They surrendered on the 30th June 1922 although fighting continued in a sporadic fashion in Dublin until 5th July 1922.

General Mulcahy returning from his honeymoon in Donegal could see that rural Ireland in the shape of Connaught was all in the hands of anti-treaty forces. 90% of IRA commandants there were anti-treaty men and had brought their Volunteers with them. Mulcahy vowed to bring Connaught back into the fold. The scene was set for this bloody internicene struggle, Ireland’s Civil War.

General Mulcahy had decided to win back Connaught from his military outpost in Athlone. The 1st Battalion North Roscommon Brigade of the IRA had taken over the civil and criminal responsibilities of the town of Boyle in late March 1922 when the British Army vacated the Barracks, now King House and the Royal Irish Constabulary was disbanded. They first of all congregated at the Work House at the top of the town where the Plunkett home is today, before taking up residence in the Barracks. During the political machinations of April/May 1922 the members of the 1st Battalion had realised where their allegiance lay. Some withdrew including their leader Michael Dockery and joined the Free State Army, most remained under the anti-treaty banner. Michael Dockery, an Elphin Man, had been leader of the 1st Battalion, North Roscommon Brigade throughout the War of Independence and had been imprisoned in King House a year before with the threat of execution hanging over him before he managed to escape across the Boyle River.

Mulcahy sent a force of Free State soldiers under Brigadier Dockery to Boyle at the end of June 1922 and they took over the Work House buildings. The Free State force although heavily armed were surrounded by a lightly armed but larger anti-treaty force who had a few handguns, shotguns and a couple of rifles.

On Saturday 1st July the Anti-treaty men attacked the Work House from the railway side but were beaten off, however Brigadier Michael Dockery was shot at close range, his body lying in open ground until a group of nuns went and brought his body in the following morning. It was on that day the armoured car “The Ballinalee” drove into town and started firing at the barracks with its machine gun. The Barracks was set on fire and the anti-treaty men pulled out and dispersed to various locations round the town as the civilian population deserted their homes in big numbers.

On Monday 3rd July sporadic fire from both sides occurred with Bridge Street acting as the centre of the fighting. Miss Ellen Nolan who lived on Bridge Street and had chosen to stay at home was struck by a stray bullet which entered her nose and blew the back of her head off. Another lady next door was struck by a spent bullet and a boy named O’Brien was shot in the thigh whilst running an errand.

On Tuesday and Wedneday, the 4th and 5th July the Free State soldiers gradually and with the help of “The Ballinalee” took over the town arrested some civilians and the officer in charge of the armoured car was shot in the hand. The anti-treaty forces dispersed and set up outposts on the Gurteen, Carrick and Roscommon Roads in order to stop reinforcements arriving. One of these outposts on the Roscommon Road was the house of a respected farmer who lived at Ballytrasna, a townland one mile out of Boyle which had an elevated position on the approach from Roscommon. The family had been forced out of the house and forced to take refuge in the war torn town.

A Free State NCO Sgt Frank Balfe was put in charge of a convoy of three wagons and sent from Athlone to bring help to the beleaguered Boyle Free State garrison. Frank Balfe, an Athlone man, had trained as a mechanic and had enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps at the beginning of the Great War. He served throughout the war as a driver ferrying men and ammunition to the front. After the war he continued in his trade as a fitter but in May 1922 had joined the new Free State Army and because of his previous service had immediately been promoted to Sergeant.

On 6th July warned of the outpost on the Carrick Road, Frank Balfe instructed his driver to turn left towards Croghan and enter the town on the Roscommon Road. Entering Ballytrasna the convoy was halted by a weak burst of fire from the occupied house. Frank Balfe shouted orders to his men to storm the house. Running up the drive he was hit in the head by a richochet bullet and bleeding from his wound Balfe and his men stormed the house with no other casualties. They captured 14 anti-treaty soldiers bereft of ammunition and led them to the Free State vehicles. On the way down the drive an anti-treaty man who had hid in an outhouse fired on the party, one of his shots killed Frank Balfe. His body was brought into Boyle where a funeral mass was said on the 7th July and his body returned to Athlone. The 14 prisoners were interned in Boyle Barracks and the town came under Free State control. The first of the towns in Connaught to come under the Free State government’s aegis.

And so ended the life of two very brave soldiers, probably the first Free State soldiers to die in Connaught and also the life of a confused civilian onlooker in what was to be a horrible conflict whose scars remain in 21st century Ireland. The family in Ballytrasna eventually returned to their house and their descendents still live there to this day.

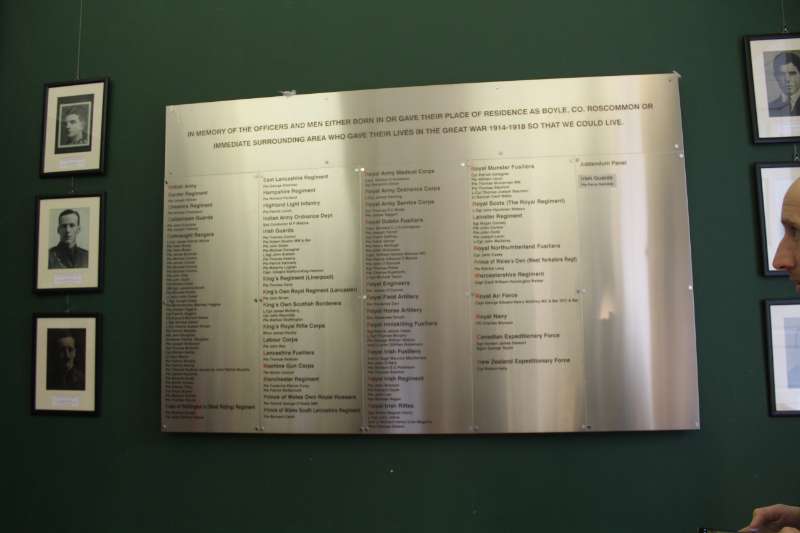

(pic from exhibition in King House March 2016)